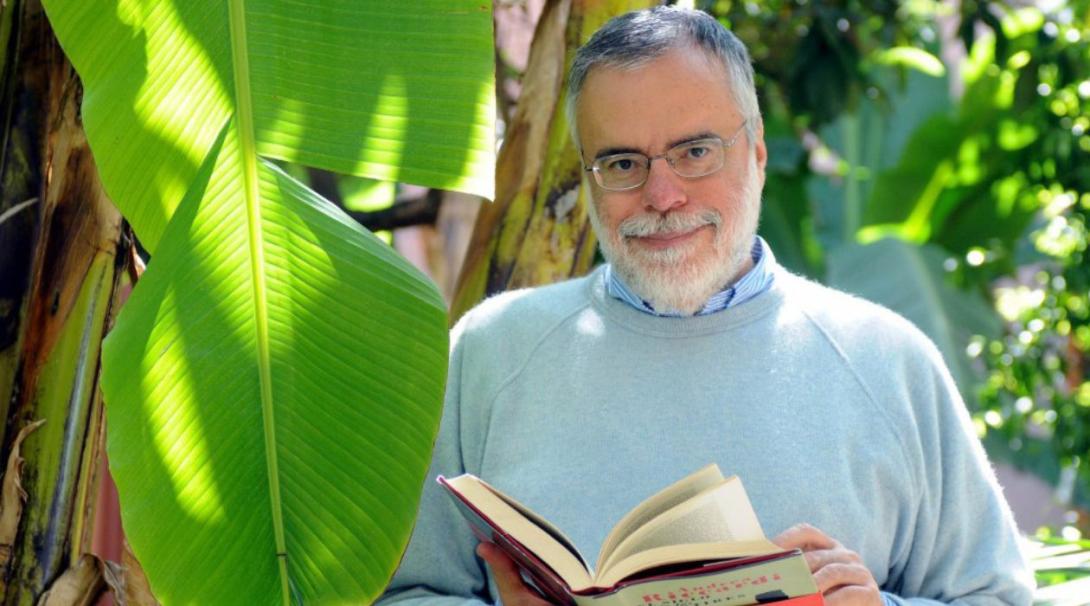

Image from www.santegidio.org

On Friday this week, New City Press publishes The Cry for Peace by Andrea Riccardi, the founder of The Community of Sant'Egidio. What follows is an edited version of an interview with the author that was first published in the Slovakian magazine of the Focolare, Nové Mesto, earlier this summer.

Your book was published last year in Italian. Many things have happened in the world since then. How is it still relevant for today?

Andrea Riccardi:

Unfortunately, yes, because there is still war in the Holy Land, there is war in Sudan, there is war in Kivu, and not just in Ukraine, because we have re-legitimized war as a tool for resolving conflicts. This is the reality.

The word peace has been erased from our vocabularies, and now in public debate we talk about weapons, about intervention, about war. It is a tragedy because I do not know where we are heading.

We think about Ukraine, which is so close to our hearts, a European country, a country to which Sant'Egidio is very attached. We have many Sant'Egidio communities in Ukraine. I have known Ukraine since the late 1980s, when it was still Soviet, and I closely followed the Ukrainians’ desire for freedom and independence. What is happening in Ukraine? It is a state in crisis, a people of refugees, there is hunger, there are all kinds of needs. Since the beginning of the Russian aggression, Ukraine is a country truly destroyed, which has resisted heroically, but deserves peace.

I think we need to find space for negotiation. After a few weeks of war, space was found between Moscow and Kyiv. That space was disrupted by the intervention of Boris Johnson. We need to imagine peace, to restore to peace its space as the purpose of politics.

In the book, you warn against getting used to war as a natural outcome of conflict. Indeed, it is about the re-legitimization of war for conflict resolution. Why, despite the many places throughout Europe that serve as memorials to the two previous wars, have we still not learned from the past?

Andrea Riccardi:

We have forgotten World War II. The generation that lived through World War II has disappeared. Our elders had a horror of war. The witnesses of the Shoah have disappeared or are disappearing. The Shoah, this industrial genocide of Jews by the Nazis, was made possible mainly because there was a world war.

The disappearance of these witnesses has led us to become accustomed to war. War seems like a game, like a play, without effort, without blood, without risks. War seems normal.

Prince Harry, whom I cite in the book, in his very successful memoirs, writes: “In my helicopter, I pressed a button, people died, but it didn’t seem like I had killed anyone.” That is war as a game, war as clean. But it is not true. War is dirty, it is blood, pain, death, and destruction. This must be known. And we must not go towards war as if towards something inevitable.

There is much talk about investing more in armaments on one side, and little or almost nothing about investing in peace…

Andrea Riccardi:

I think there is an ancient art, which is diplomacy, contacts between states. Who is talking to Moscow? We need to resume and invest in diplomacy, in diplomatic initiatives.

I believe that the military apparatuses, still, the West and Russia, are talking to each other. But it is too little. We need to resume contacts; we need to talk. Because today’s wars are not like yesterday’s wars. Today, wars are eternalized. Today, wars with powerful weapons in use do not end. Just look at the Israeli-Palestinian situation: a neverending war. We do not want this for our beloved Ukraine.

If you enjoyed this article, you might like...

However, there is also a right to defense. Today, there are some NATO weapons being used by Ukraine to defend itself. On the other hand, in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Israel’s response was disproportionate to Hamas’ attack in October last year. What limits should there be to defensive war?

Andrea Riccardi:

I would not frame the discussion in this way. I would not pose the problem of the limits of defensive war; I would pose the problem of how to bring the ceasefire and peace closer. This is the real problem, and I see that it is not coming closer. So the discussion of limits is merely theoretical.

The limits have been exceeded. In some way, when a man dies, when a child is killed, the limit is already exceeded. What I emphasize is that nothing is being done to bring peace closer. And then, above all, there is a collapse of culture. The twentieth century, with all its terrible contradictions, left us the idea of the unity of the world and of peoples. The pandemic confirmed that we’re all in the same boat. This is an experience that each of us has had, but then we turned the page and resumed this individualistic and nationalist race.

We must win peace. Peace must be built; peace is not given. Peace is not for cowards. It is for the brave.

Various popes have questioned the concept of a just war. How do you see the Pope’s position on this issue in the context of current conflicts?

Andrea Riccardi:

All the popes of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries have maintained that war is an adventure with no return. And this differentiates them from other Christian Church leaders who have often taken nationalist stances.

Why have the popes maintained this stance? Because they know that war is an adventure with no return. Because they know that war is an unpredictable game. But the popes have not called for disarmament, the abolition of armies. They know the complexity of politics, but they insist on the road to peace. They speak of just war, not of a crusade, because today every war is blessed by some religion. The just war, in Catholic tradition, was blessed by the Church. Today, it is blessed by the leaders of all religions: Christian leaders, Islamic leaders, Jewish leaders, Hindu leaders. In short, religion is the last resort of justifying war, and this is a great responsibility of religions.

I am convinced that Pope Francis, who speaks of peace, is often misunderstood. But peace is part of politics, it is not an idealism, and in this sense, the Pope speaks also of diplomacy and negotiations. In this sense, he speaks with everyone: with the Russians, with the Ukrainians, with Western leaders. He has always maintained that the path of dialogue, the path of negotiation, as the only possible path. And there are no sacred wars.

Is it possible to encourage the development of cultures that favor peace?

Andrea Riccardi:

One hundred years ago in Slovakia, Hungary, Bohemia, Poland, and Germany there was a very lively culture, an extraordinary culture. But culture has withdrawn into the cultural industry; it has not become social culture; it has not become culture of life; it has not become culture of behavior. The pandemic has reduced many things to pre-pandemic levels.

I believe that culture has a role in this. Not the culture of talk shows or social media, but the culture of thought, the culture of engagement, the culture of responsibility, the culture of freedom. And I believe that the Pope is creating a culture of fraternity. We need fraternity.

The Pope is accused of talking too much about fraternity and love. But fraternity and love have been relegated to the church. I believe that fraternity and love must become political goals. This is very important. The future is for fraternity and love. This culture must be re-established. And for me, this means humanism. This is why it is so important to support Europe. Europe has deep roots in this humanism. Europe must defend itself from nationalism. Europe has a great humanistic vision, and we must believe in it.

Many intellectuals, artists, scientists, politicians, and entrepreneurs speak in the book about their commitment to peace, humanity, and respect for life. In your opinion, is this a commitment of society as a whole? And how can it be strengthened?

Andrea Riccardi:

It is a commitment of society as a whole, it is the mobilization of society, it is the transformation of society. It is not a battle for the elite, but it is about transmitting this culture to everyone. And I believe that we can only achieve this if it comes from a variety of directions.

The culture of dialogue, peace, and fraternity must penetrate the walls of schools, of universities, of the media. I think this is a very important point.

The Pope recently said that peace must enter politics, but politics must enter schools as well. When we were kids, we read history books about the Second World War, but today, where is this culture? It must be re-ignited. And peace must be seen as an achievement. We must win peace. Peace must be built; peace is not given. Peace is not for cowards. It is for the brave.

I believe that peace is the strength of the world. We must believe in peace as a goal and build a humanistic culture that favors peace. So, this is not just a battle of the elite. It is a culture that we must convey to the young. I think this is very important, and I think it is possible. Let us believe in it and work for it.