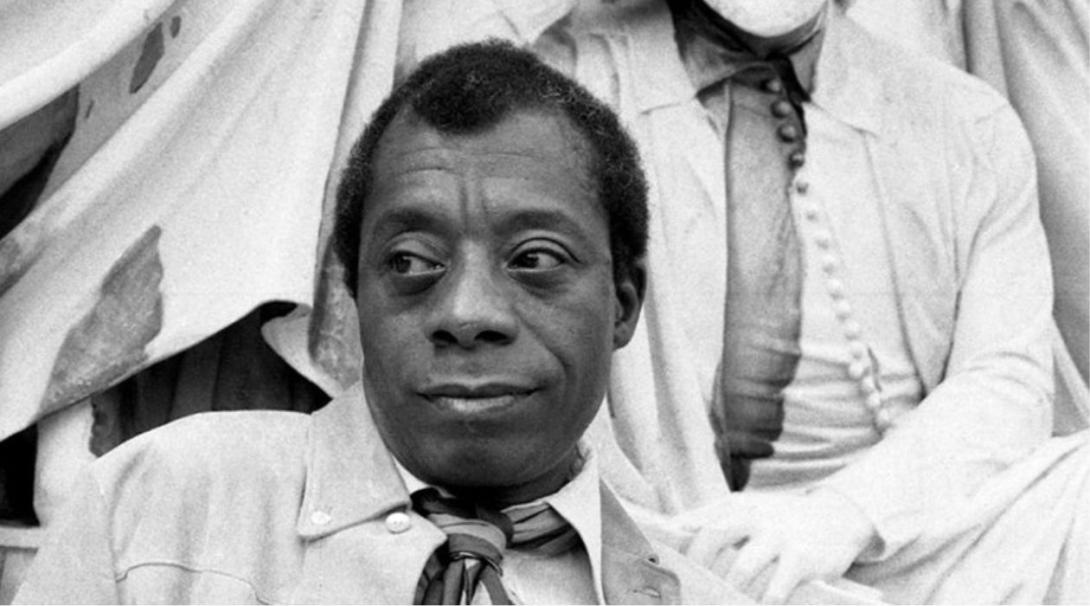

Albert Warren/Wikimedia Commons

October is Black History Month in the UK, and recently I was part of a panel on BBC Radio discussing this year’s theme, “Reclaiming Stories.” As in most places in the West, British history is often composed primarily of white stories. Black stories, writers, artists, and heroes are often siloed away from mainstream awareness, and the organizers of Black History Month here recognized that not only is history incomplete when the full truth isn’t known, not only does the larger culture lose out on the inspiration of great stories from the margins, but ignorance makes it entirely too easy to ignore or to perpetuate injustices. Democracy depends on the truth.

The great twentieth-century writer James Baldwin took history as one of his particular themes. I teach Baldwin to university students, and write about him often.

He was born in Harlem, but lived much of his life in exile in France, for it was clear to him that however gifted, artful, and articulate he might be, his own story would always be marginalized in the U.S. Baldwin wrote to wrestle with injustice with the conviction that people must know and acknowledge their real histories. A truthful reckoning, he often said, involved full understanding of history’s bright and dark corners, as a precondition to any further action.

So it is that I look at current trends to hide those dark corners (and as disturbing, to offer mistruths about our present reality) as one of the most dangerous movements in our current communal life. Across the American South, for example, state legislatures have passed bills banning the teaching of stories/histories that might be offensive to students (by which, unsaid but understood, they mean white students or their parents), and states adopt history textbooks that avoid or distort the past realities of slavery and other difficult topics.

A truthful reckoning, he often said, involved full understanding of history’s bright and dark corners, as a precondition to any further action.

In my home state of Texas, the legislature has passed a bill banning docents at the Alamo from teaching that the defenders of the Alamo were slaveholders or that Texas’ glorious fight for freedom, one of my state’s formative myths, was fought largely to maintain chattel slavery, which Mexico had banned. I have lived in Texas for almost 40 years and teach at Baylor, chartered before Texas became a state, but I had not known this essential fact about the war for Texas independence until recently.

This incomplete history is egregious, as are most attempts to retell American stories in a way that feels more acceptable to white Americans. Last year, the Florida State Board of Education approved history standards teaching that slaves benefited from their enslavement because some of them learned valuable skills. The fact that some enslaved people may have learned to bake, farm, or build during their captivity does not set aside that captivity, and this decision diminished the full horror of slavery.

When the whole truth—past truth or present—is kept from a people, when we fail to know and reckon with all our stories, our life together suffers. “Know your history,” Mr. Baldwin counsels. Justice, democracy, and faithful action depend upon it.