Photo by courtesy of Cyprian Consiglio, OSB Cam.

My monastic congregation has a community in South India. Since it is one of the forerunners in enculturation, it is referred to as an “ashram” rather than a monastery––the Ashram of the Holy Trinity. It’s also known by two other names, Saccidananda Ashram, and then the name it is usually called––Shantivanam. Saccidananda is an Indian descriptor/name for the Divine made up of three Sanskrit roots, sat, chit, and ānanda, which mean Being, Knowledge, and Bliss. The three founders of the ashram, Jules Monchanin, Henri le Saux (Abhishiktananda) and Bede Griffiths, saw in that Hindu appellation an intimation of the Holy Trinity. The name Shantivanam also comes from two Sanskrit roots, shanti and vanam. That is the name of the place itself––“forest of peace.”

I had been there ten times between 2000 and 2012. I was first sent by the General Chapter of my congregation to help with liturgy and music. Soon I began to use a phrase I got from the Upanīshads, one of the sacred texts of India, to describe what I did there: I was “learning and teaching.” I always offered my services to the community in whatever way they desired, usually formation work or teaching English. But I was really there to absorb and learn, not so much from books but from the spiritual genius of the Indian culture. I have been a long-time student of the thought of Bede Griffiths, so it has always been very moving for me to be a part of the continuation of this incarnation of his dream of a “marriage of East and West,” not to mention to be where he spent so much of his life, surrounded by the same sounds of the forest, as well as his cell, his books, and other personal effects.

I served for ten and a half years as prior of my community, New Camaldoli Hermitage in Big Sur, California. I told my Indian brothers––and sisters—there is a women’s community called Ānanda Ashram across the road––that I wouldn’t return to Shantivanam until I’d completed that service, since travel in India is often taxing and it barely seemed worthwhile to go for under a month. But, true to my word, as soon as I began my year-long sabbatical at the end of my term as prior, India was my first stop.

Actually, my first stop was really Singapore. I remember a time when I used to say that I didn’t know where Singapore and Malaysia were, but now I have friends and acquaintances all over the island and up and down the peninsula.

You see, the plane trip from California to Chennai is excruciatingly long, usually with a layover in Korea or Japan. But on an earlier trip, I’d had a long layover in Singapore instead. I was exhausted from the flight, but quite impressed by how nice Changi Airport was, and how verdant and beautiful the island itself was. So on a subsequent trip, I asked if there was a chance I could find a place to stay for a night or two in Singapore on my way to India. The next thing I knew I received an invitation to offer a concert for a parish there, and thus started the beginning of several wonderful relationships, many with folks who were associated with the World Community for Christian Meditation and others with people involved in interfaith dialogue. (Singapore boasts of nine major religions coexisting peacefully.)

My new friends in Singapore then introduced me to their friends across the strait in Malaysia (at one time the two were one country) and I consequently did several retreats for the WCCM there as well and a few series of concerts up and down the peninsula.

This time in Singapore, though, it was more leisure than work. Friends treated me to a hotel room in a section of town known as Little India, a fitting neighborhood to prepare me for my next stop. Not only was it the first time I was truly on my own in the city, which was great fun exploring on foot, it was also during the first days of Ramadan. Hanging out on Arab Street, a short walk from my hotel, was fascinating, especially in the evening when you “can’t tell a white thread from a black one” and the fast breaks with the evening meal known as iftar, usually taken from food stalls outside surrounded by crowds of people in a wonderful festive air.

In India itself, the bulk of my time was at Shantivanam, and here too this time the expectations on me were quite minimal. I was simply delighted to be with the community again, participating in the long communal meditations in the early morning and evening and the samdhyas, the prayers that take place at what are considered to be the particularly strong hinge moments of the day, between night and morning, morning and afternoon, day and night. By special permission of the church in India, the liturgies there, as in other Christian ashrams, are adapted to Indian style more than they would be in a parish.

We always sit on the floor, for instance. There are many Indian micro-rites worked into the ceremonies such as the waving of flames, the offering of flowers, and marking the forehead with sacred colors or ash; there is the regular singing of beautiful Christian bhajans, simple devotional songs. Elements from other traditions are also incorporated. Before each liturgy a reading is done from one of the non-Christian sacred texts of India, for instance; and Sanskrit chants (not ones addressed to Hindu deities) are sung to begin samdhya.

I remember a time when I used to say that I didn’t know where Singapore and Malaysia were, but now I have friends and acquaintances all over the island and up and down the peninsula.

One thing has always struck me there, and it did again this time even more: you can live in a way that is so simple and direct, at least at the ashram, with the bare minimum of creature comforts, that I have always found so freeing, but that would seem so eccentric and abnormal in the West. Fr. Bede especially wanted to make sure that the life of the residents of the ashram did not far exceed the standards of the villages that surround it. It’s hard to overstate the profound effect that kind of unpretentious austerity has on one’s spiritual practice.

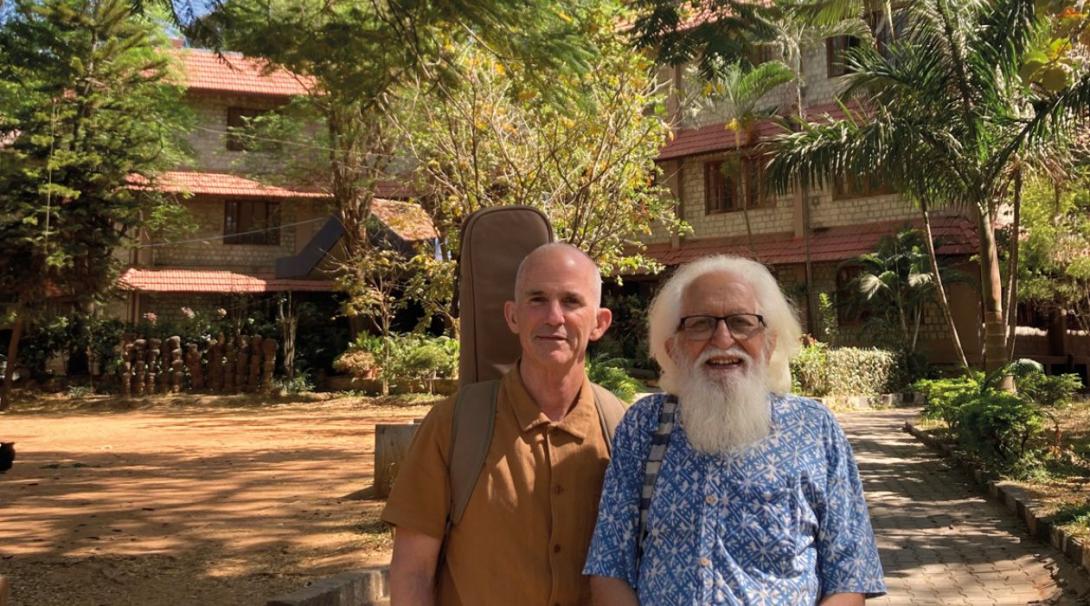

I had two other stops in India after my three weeks at Shantivanam. First, I took an overnight train to Bangalore, which is sometimes referred to as “the Rome of India,” and spent a marvelous day with a man named Jyoti Sahi. Jyoti is the best-known living Christian artist in India, a fine scholar and church architect among other things. He and his English wife Jane have a long history with Shantivanam and its founders, and I spent the bulk of my time with him simply absorbing wisdom and luxuriating in the stories he told of the early days of what is known as the “Christian ashram movement.” I then went up to the north and made a week’s retreat at a lovely ashram right on the banks of the Ganges before heading back east to Singapore––and then Malaysia.

Friends in Malaysia arranged for me to do four musical presentations whose purpose was a Lenten reflection and a preparation for Easter. They were wonderful events, a combination of singing and teaching. Of everywhere I have been in the world, I find that Malaysians are the most eager singers I have met, easily and quickly joining in on the song refrains that were projected onto an overhead screen. In addition, I find them so deeply demonstrably appreciative and incredibly hospitable. I suppose being a minority in a majority Muslim country breeds a certain tender, even jealous, love for one’s Christian faith.

Recently I was reading “Dialogue and Proclamation,” issued by the Pontifical Council for Interreligious Dialogue (now known as the Dicastery for Interreligious Dialogue) in 1991. It warns that one of the obstacles to the proclamation of the Gospel can be that in some Christians there is “an attitude of superiority which can show itself at the cultural level” and “might give rise to the supposition that a particular culture is linked with the Christian message and is to be imposed on converts.” I immediately thought of these, my latest experiences in southeast Asia, that once again remind me (and warn us!) how narrow our own view of Catholicism, of Christianity in general can be in the West, and in America specifically. There are so many beautiful creative ways to incarnate the truths of our faith and express our devotion.

As the Persian poet Rumi wrote, “There are hundreds of ways to kneel and kiss the ground.”