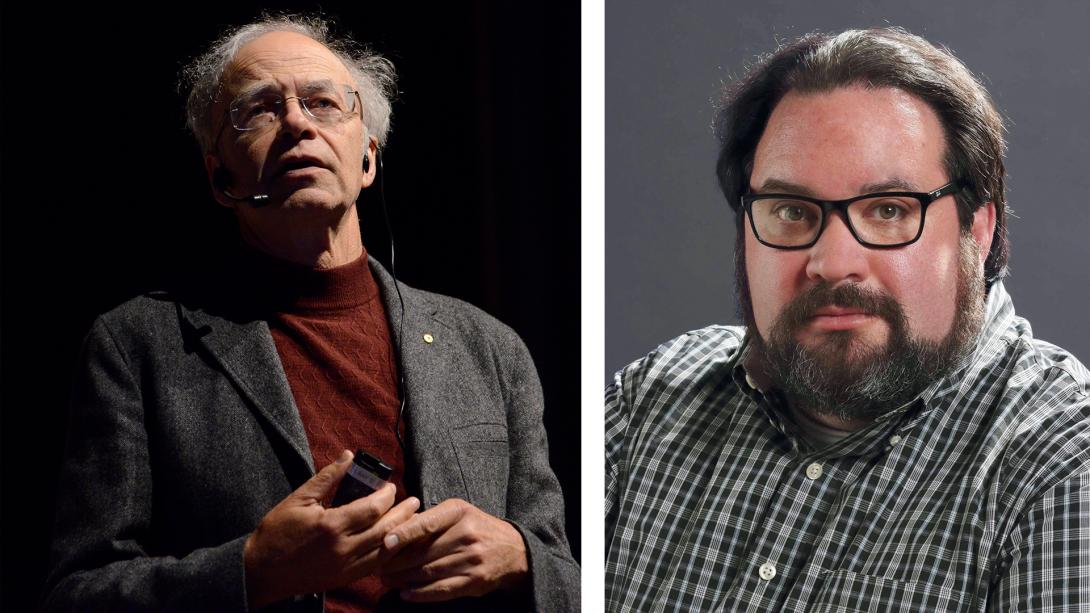

© Photo by wikimedia.org

©Photo courtesy of Charles Camosy

This was conducted by Susanne Janssen. Peter Singer is the Ira W. DeCamp Professor of Bioethics at Princeton University. His classic work from the 1970s, Animal Liberation, was just launched in an updated edition: Animal Liberation Now (HarperCollins). Charles C. Camosy is associate professor of theological and social ethics at Fordham University.

What are the most significant ethical mistakes that our society makes today? Where are we acting in a short-sighted manner?

Peter Singer: I think the basic mistake we make ethically is to focus too narrowly just on ourselves, on our immediate circle of friends and family. Given the situation in the world, it’s a bad mistake for people living in affluent societies—what we can do to help would make a much bigger difference generally if we go more widely. Think of families in low-income countries who are living on about $2 per day. We have the capacity to make a life-transforming difference to them.

I also think it’s a mistake to limit our concern to our own species. We live on this planet with billions of other sentient beings. We have a huge influence on their lives, and we cause a vast amount of unnecessary suffering on tens of billions of animals. And as long as we don’t consider that, I don’t think we can say we live an ethical life.

Charlie Camosy: Animal liberation is one of the key areas where Peter and I have found serious common ground, as well as with the broader question of global poverty. One of the most important things I try to teach my students is how close Utilitarians and Christians are when it comes to our focus on global poverty. However, there is a sort of uniquely Christian focus on the local: Thomas Aquinas says that, all things being equal, we should focus on the local. However, the key point that Peter and I make is that when the need is so overwhelming, you have a very strong moral obligation to help—it doesn’t matter whether it is across the world or next door.

So how would you define the value of life—are there various degrees? Should we make a distinction between human, animal, and plant life?

Singer: I don’t make a distinction as such between members of the species Homo sapiens and non-human animals who are sentient beings, and in some cases will have cognitive capacities that are higher than some members of the species Homo sapiens. I don’t think just being human makes the difference.

But I do think that the wrongness of ending a life does vary to some extent with those cognitive capacities. Some beings live “biographical lives”; they are aware of their lives as a continuing story and they plan for their future. Other beings can feel pain and suffer but live in a moment-to-moment way.

When it comes to plants, I don’t believe that plants are sentient, conscious beings although I’m aware that not everybody will agree with me. And so I don’t think there is anything intrinsically wrong with taking the life of a plant, which doesn’t mean that it wouldn’t be a tragic thing to cut down one of the Giant Sequoias in California or some of the ancient trees we have in Australia…

Camosy: This question gets us into some of our important differences, and one of them is that there are objective goods about plant life in a Christian worldview, for instance. Creation itself has value because God said so, he pronounces these entities good.

But of course, some beings are significantly higher than others. A stone is good; it is created by God, but not in the same way as a tree. The tree images God in a way that a stone does not because the tree is alive. Living things mirror God’s existence more substantially.

And human beings mirror God in a very special way; they bear God’s image and likeness. Again, I invoke Aquinas here: he talks about the capacity “to know and love” as the kind of thing that human beings have by their very nature.

It is true and Peter has pointed out in many different contexts that certain human beings, because of cognitive difficulties or diseases, don’t seem to have the capacity to know and love even compared to other animals. But that is another disagreement that we have, and about which Christian tradition teaches: it’s about the kind of creature that you are; not necessarily what capacities you have at any particular moment.

How would you define the value of a human being? I guess you both might have a different set of criteria to answer that question.

Singer: I think we do have a different set of criteria, as Charlie just indicated. Charlie wants to look at the kind of being you are, in the sense that includes what you might have become had things gone differently. We Utilitarians are more likely to look at what individuals actually are or what they could predictably become, with capacities for sentience, for enjoying life, or feeling pain.

Those are the kinds of criteria that I would use and obviously, we can argue about that. For me, they’re not engraved in stone. They’re a matter of using our reasons to try to work out what is important in life and what is lost when the being’s life is taken.

Camosy: I think it’s important to underline that even if the tradition says that human beings are higher on the hierarchy of value, that doesn’t mean domination of other beings. The Catechism of the Catholic Church, for instance, says that we owe animals kindness.

So yes, human beings matter more than other animals. But it certainly doesn’t follow at all that we can kind of do whatever we want and torture them in factory farms because it makes us slightly more money.

In some ways, the fact that we’ve been put in this high position indicates our need to be caretakers and wit-nesses—our status gives us even more responsibility to care for animals.

Singer: It’s good to see that the Catholic Church seems to have been moving away from the idea that because God gave us dominion over the animals, we’re not answerable to God for what we do to them. That led us to a very brutal attitude to non-human animals. Pope Francis’ encyclical Laudato si’ was a very clear step in putting that interpretation of man’s dominion into the dustbin of history.

Camosy: Certainly, the Church has some blame. But the primary culprit for how we’ve ended up in this horrific place is the Industrial Revolution and capitalism; making of animals “something” other than God’s creatures: just protein units per square foot.

Singer: It’s certainly true that it’s not as if animals are better treated in China where the Church has far less influence. But I’m still waiting for somebody who has an important influence in Christianity to say that a good Christian would not buy food made from factory-farmed animals…

Peter, is there a value in suffering for you—can suffering lead to something good?

Singer: Suffering can lead to something good, undoubtedly. There can be instrumental value in suffering, but it’s not always the case.

And that’s another area where Charlie and I would disagree. I’m a supporter of medically assisted dying or euthanasia because I think if somebody knows that they’re dying, that they have a short time to live, and they are suffering and they don’t want to go on to the very end, I think it’s reasonable to help them to die. And the laws should allow that. That’s one case of suffering where I don’t think there’s value in it. But very often we do learn from suffering. We go through it and we’ll get stronger. And sometimes, of course, it’s a warning to us to change our lifestyle.

I did a podcast interview with a man called Rich Roll who was a drug addict and went through really bad times. He got through it and is now a vegan, ultra-marathon runner, living a very good and worthwhile life. In his case, suffering strengthened him. But it’s an instrumental value for me, not an intrinsic value.

Camosy: I think if one is a Christian, one can find some kind of solace in suffering as it connects you to Christ’s suffering. But I want to distinguish any discussion about that from the use of physician-assisted killing because the Catholic Church is one of the foremost providers of palliative care in the whole world, just focused on trying to lower the suffering of people. The opposition against physician-assisted killing has nothing to do with the good of suffering. It’s about an objective, moral norm against killing the innocent.

Looking at the spike in polarization and anger in our society—do you think we’ll make it to work together to resolve the issues that we need to resolve to have a future? What gives you hope?

Singer: I’m sure that it is possible for us to change, to live and act more ethically. I’m not sure whether we will, because it’s very hard to predict the future. One big issue we haven’t talked about at all is climate change. I’ve just been reading a book in which the author is talking about the losses that have already occurred, like the terrible wildfires and floods we’ve had in Australia, and the perhaps irreversible changes to the Great Barrier Reef. But the book is balanced between that kind of really depressing fact and the possibility that it’s not too late to avert the worst developments. I think there are a lot of people who want to do that. But can I be confident about that? Unfortunately, I can’t.

Camosy: I have a very similar kind of reaction. One of the big frustrations that I have is that we sort ourselves into us versus them; right versus left; conservative versus progressive. I’m no fan of Donald Trump, but one thing that happened as a result of his presidency is that it scrambled our political categories. It’s not even clear what a Republican or a Democrat is anymore. And to me, that’s a good thing. It’s a way of breaking down a hopelessly simplistic, toxic imagination. We’re going through growing pains to find out what’s next, but it will be something other than a right versus left fight if we acknowledge nuances, complexity, and good people on multiple sides, and if we focus on issues rather than on political sides.