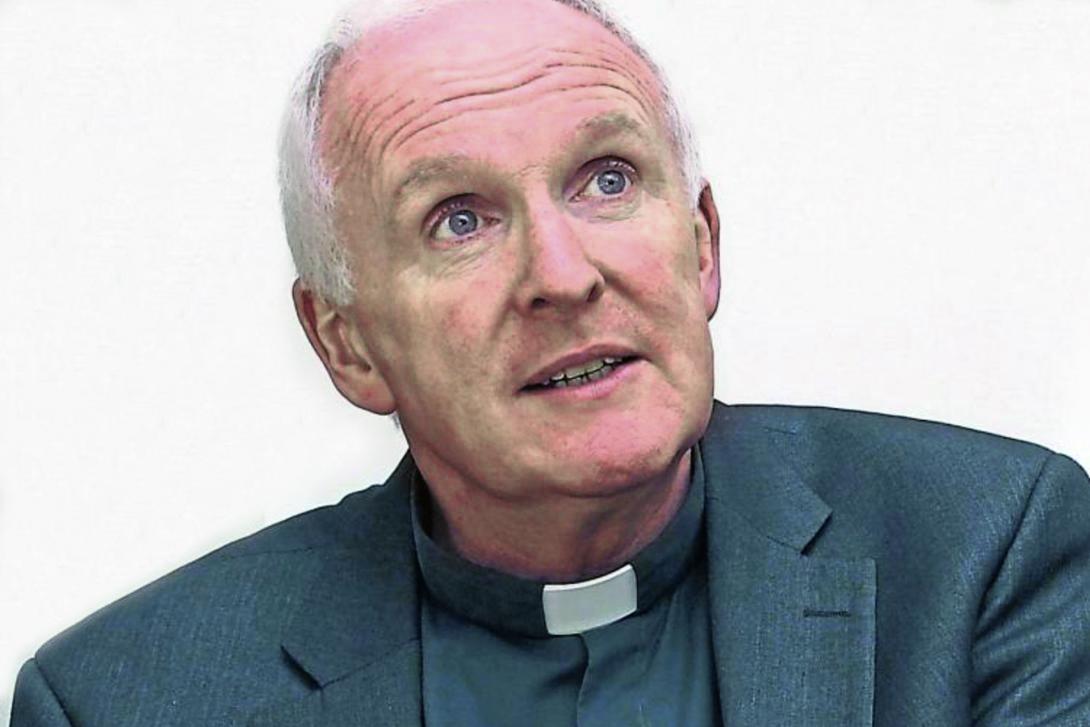

An interview with Bishop Brendan Leahy about the abuse scandal in the Catholic Church and its consequences

Photo by limerickdiocese.org

You have had quite a few experiences of pastoral life in Ireland where the Catholic Church has, for some time now, faced abuse scandals. Could you share one?

One of my first experiences goes back to 1995, when the first public scandal involving a pedophile priest in Ireland erupted. I was asked by the archbishop to go and help out in that parish. It’s hard to describe the range of feelings I met there—anger on the one hand, a desire to defend the accused priest on the other. Many people felt betrayed, confused, hurt.

Together with another priest in the parish, we started visiting the families of the altar servers… I soon felt quite overwhelmed by what seemed to me to be an impossible situation. It seemed like whatever I did or said was wrong in the eyes of one or other group of the parishioners.

One day, however, I gained an insight that helped. An American priest psychologist, Stephen Rossetti, was invited to hold a conference in our diocese, and he explained that when a pedophile scandal explodes in the Church, it becomes like a lightning rod that attracts everything negative that people have ever felt towards the Church. Past wounds can surface, even if they have nothing directly to do with pedophilia.

Thinking about this, I remembered that Chiara Lubich had once said that Jesus crucified and forsaken [referring to the moment when on the cross Jesus cried out, “My God, my God why have you forsaken me.” (Mt 27:46)] is like a lightning rod. He took upon himself all that was negative—betrayal, impossible situations, lack of any help—and he consumed all of this in himself out of love, transforming everything into love. He became a wound in order to heal every possible wound.

I realized that, with God’s grace, in some small way I could be a little like him. I too could become a lightning rod and let the negative reactions strike me, then hand them over, as Jesus did, into the Father’s hands believing in his love.

With that I felt I could start over again, go outside of myself and establish new relationships with the people who felt so betrayed by the Church. And little by little I began to see new shoots of life emerge in the parish.

What remains in me most from that time is the realization that the Church is not simply the result of all our activities. Rather, the Church is something we generate by loving Jesus Forsaken.

Pope Francis’ visit to Ireland in 2018 for the World Meeting of Families in Dublin marked an important step. Could you describe it?

In the days leading up to the pope’s visit, the newspapers were filled with many articles criticizing the Church. A shocking report on abuse came out of Pennsylvania, and then there was the removal from office of the former cardinal archbishop Theodore McCarrick.

As the weeks went by and the pope’s visit was drawing closer, recognizing that many people still felt deeply wounded by the failures of the Church, two thoughts came to mind. First, I remembered something that the German Bishop Klaus Hemmerle said on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Kristallnacht operated by the Nazi Party in Germany. In his prayer, Bishop Hemmerle used the words, “My people did this.” Second, I also recalled something that Chiara Lubich wrote in a text of her Paradise ’49 experience, “For every mistake made by my brother or sister, I ask forgiveness of the Father as if it were my own because my love takes possession of it.”

I felt it was important to try and listen more to those who in silence were crying out in pain because they felt betrayed by the Church in its institutional role.

To make a long story short, after sharing my idea with a fellow bishop, I promoted a pilgrimage to an historic and sacred place in the diocese that reminds people of the long history of the incarnation of the Gospel in our country. In a moment of public prayer, I expressed horror over what had happened in the Church, and I asked forgiveness from God and from those wounded by it. At the same time, I emphasized the call that reaches us in the Risen Lord to renew, or better, to repair the Church and rekindle hope. To tell you the truth, it was very hard for me to even name this evil or talk about the damage the Church had done. However, this event had a positive outcome and attracted media attention.

At that time, I was also struck by a passage I read in Pope Francis’ apostolic exhortation Gaudete et exsultate: “Humility can only take root in the heart through humiliations” (118). Of course, God is not intent upon humiliating us. God loves us immensely. But it can happen that we are humiliated publicly, and perhaps at times irrationally. But everything has a purpose. Humiliations help make us more humble.

In the course of your ministry as a bishop you have met both with those who have committed acts of sexual abuse as well as those who have been abused. What comes to your mind when you think of all this anguish?

It’s heartbreaking to meet a grown man who cries like a child when he talks about the abuse he endured. There are no words. I feel profound regret for what happened in the past, yet I also recognize that relating to those who have suffered abuse or who committed it is never easy.

I remember that when one of the first reports commissioned by the government was published, I thought, like a true theologian, of writing a good article that would help everyone put the situation into context and provide keys to help them interpret it. But then I realized that it wasn’t simply a matter of contextualizing painful situations into a nice neat intellectual package.

I had to a let myself be penetrated by the painful cry of those who were suffering. I’m not sure how capable I was of doing this, but one thing for certain became quite clear to me.

On the one hand, in the light of what Pope Francis calls us to, I feel a strong desire to go forth into society’s peripheries and help the immigrants, the homeless, prisoners, drug addicts etc. and put into practice what today we call the ‘option for the poor.’

And yet I realize more and more that such actions could for me be a source of consolation, almost as if I could be saying to myself: “Here I am doing good for others, helping the disadvantaged, etc.”

But encountering the situations of abuse is different. I find myself directly involved, as it were, covered by shame, aware that I too am inside this extremely painful existential periphery that makes me wounded among the wounded, and brings me to experience weakness, limitedness, perplexity.

I know that the work done in this field will for the most part remain hidden and will not earn me public esteem. But it’s what God wants from me today.

These times of great change could bring us to dream and look beyond today, or it could cause great uncertainty. What gives you hope?

In the first place, faith itself. Looking at the present Church situation, I can’t fool myself and talk about things with a simply human or superficial optimism. The problems are real. But faith in God who is love makes me say, “God has a plan, and it is important to believe in it and not allow ourselves to be discouraged by the problems.”

Aldo Stedile, one of Chiara’s first companions, at a meeting I attended in Rome for young priests, once used an image that struck me, relating to the primacy of belief in love. He described how when you’re buttoning your shirt, it’s important to get the top button right, otherwise all the other buttons will be out of place. I was struck by that image. To believe in love, one could say, is to fix well that top button of our Christian life.

I find another reason for hope in the history of the Church. It’s enough to think of the history of the people of Israel: think of all the dramatic moments they went through. Then we can read about the dark moments in all our churches, in the lives of the saints and in the religious orders and movements. We need to remember that the religious order of the Jesuits was actually suppressed by a pope for almost 40 years. Afterwards a new season of growth began, to the point that today our pope is a Jesuit.

Ireland has lots of tourists interested in visiting ancient historical places like monasteries and cathedrals, where all that’s left now are ruins. Looking at these ruins, two things came to my mind: the configuration of the Church changes. It has moments when it flourishes and others when it seems to be crumbling.

I like that saying of the English Cardinal John Henry Newman, that the Church always seems to be dying but then always seems to be rising against all human calculation. Perhaps somewhere today in places such as Africa, the church is experiencing enormous vitality; in other continents it might be a time of discouragement. But it’s always the same Church.

Despite everything, the Church moves on. We’re seeing now how much more the culture of synodality is advancing compared to 50 years ago. And we can also say, as painful as it is for us, that the fact that the Church is facing up to its defects, limits and abuses is a step forward. Every generation has its own cross to bear.

Brendan Leahy

1960 born in Dublin, Ireland

1983 graduate of the University College Dublin Law School

1993 defended his doctoral thesis on the Marian profile of the Church at the Gregorian University, Rome

2013 named bishop of the Diocese of Limerick, Ireland

2015 nominated co-chair of the Irish Inter-Church Meeting

2016 organized a diocesan synod in Limerick

2021 named deputy chair of the Steering Committee of the Synodal Pathway of the Catholic Church in Ireland

2022 nominated a member of the Congregation for Catholic Education

First published in Città Nuova, Italy.