When I was a child, my father always set up an elaborate Christmas scene at home. Brown paper bags became hills; pieces of a broken mirror became a river; freshly picked moss became fields.

Far off in the background stood Herod’s palace. Along a sandy path, three figures rode on camels; in the fields, shepherds watched their sheep; a man fished by the river. Closest to us sat a crèche.

It was a magical time. On Christmas Eve, we were allowed to move the shepherds to the stable and the Magi could come closer, but not too close: their journey would last for the 12 days of Christmas. On the 12th day, as they had done so long ago, the three kings would bring gifts, but this time their gifts were for all the children in the land.

This memory made me reflect. What was that first Christmas really like? I began by considering the poverty of Joseph and Mary.

We think of Joseph as a carpenter, with the image of what a carpenter would be today. But renowned biblical scholar John Dominic Crossan, in an interview for PBS’s Frontline, pointed out that Jesus was born in an agrarian society. The term used in Mark’s Gospel in Greek (tectone) is closer to handyman or jack-of-all-trades.

If Crossan is right, this would mean that Joseph had no land and had to rely on odd jobs for survival. He would have been at the bottom of the economic scale.

Could Joseph have even afforded a donkey? Or did Mary walk the 90 miles (145 km) between Nazareth and Bethlehem? The Gospel of Luke simply says that they traveled to the City of David. We don’t know. But I wonder.

And was there no room in the inn? Really? Or was this a case of the innkeeper not wanting riffraff under his roof? But seeing Mary’s state, he allowed them the stable.

I closed my eyes and imagined myself entering the stable. The first thing that hit me was the stench, not unlike fields spread with manure in the spring, but stronger. The ground covered in filth.

I imagined Joseph, shooing away mice and gathering straw for Mary to lie on, before cleaning a spot in the manger for their newborn child. The shepherds arrived, poor like Joseph and Mary and carrying the smell of their sheep. Perhaps it was logical that they should be the first recipients of the good news.

As if all this wasn’t enough, Joseph then gets wind of Herod’s evil plan to kill all males under two, and so he and Mary must flee, becoming refugees in a foreign land.

This is how God chose to enter human history.

In his last Christmas sermon in 1979, St. Oscar Romero reflected on this mystery. “When John the Baptist sent his disciples to ask the redeemer, ‘Are you the one who is to come, or should we look for another?’ Christ sent them back with the answer: ‘Tell John the Baptist what you observe: the blind see, the lame walk, lepers are cleansed, the deaf hear, the dead are raised—and most marvelous of all—the poor have the Good News proclaimed to them! And blessed are those who take no offense at me’ (Luke 7:20, 22–23).

“This is the message of Jesus who was wrapped in cloth and laying in a manger, poor as the poorest of the poor. I don’t think that even the poorest people are born in caves on a cushion of hay, but for Jesus there was not even a decent bed where his poor mother could bring him to light. The penniless Christ wrapped in cloth is the image of the God who humbles himself.

“This descent of God has great meaning for us tonight. Let us not seek Christ in the opulence of the world or among the idolatries of wealth. Let us not seek him in the struggles for power or among the intrigues of the mighty. God is not there.

“Let us seek God where the angels say he is: lying in a manger on a little straw, wrapped in the poor bit of cloth that a humble woman of Nazareth could afford. There, we find resting a God who became man, the king of the ages who makes himself available to us as a poor child.

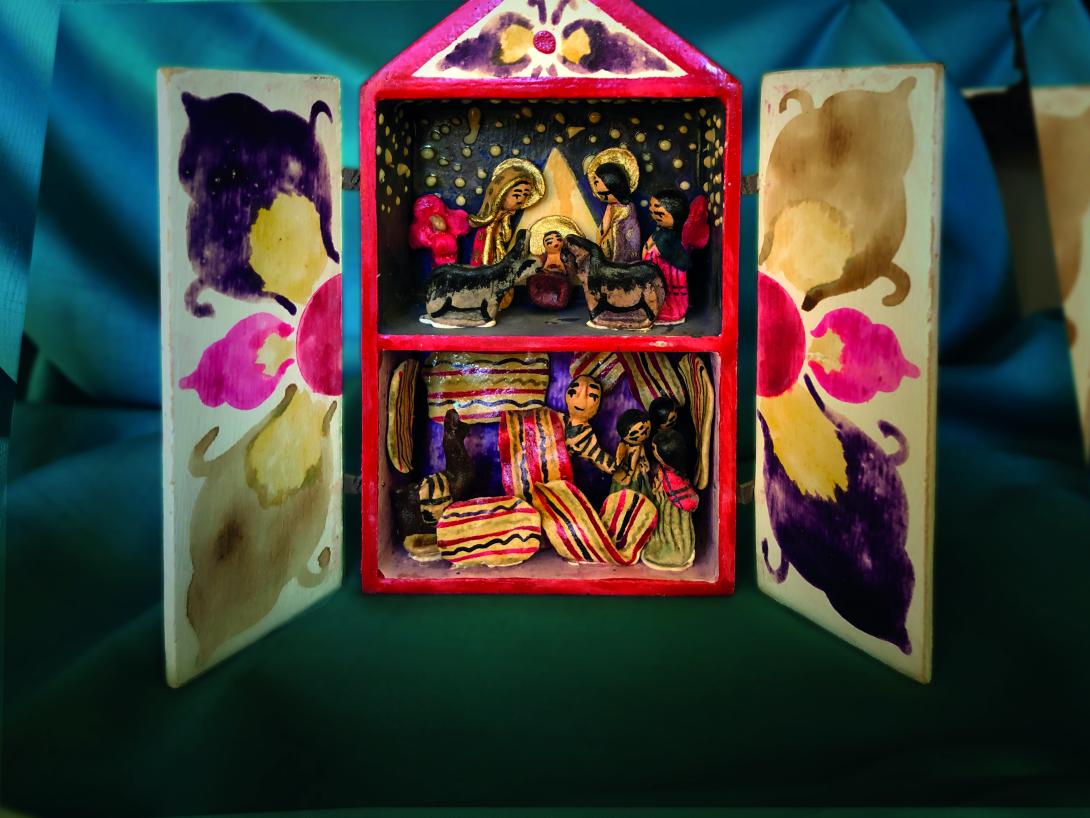

“If we want to find the child Jesus today, we shouldn’t contemplate the lovely figures in our nativity scenes. We should look for him among the malnourished children who went to bed tonight without anything to eat.

“We should look for him among the poor newspaper boys who will sleep tonight on doorsteps, wrapped in their papers. We should look for him among the poor shoeshine boys, who have perhaps earned enough to buy a little gift for their mothers. Or who knows, maybe some of those boys failed to sell all their papers and will be given a tremendous scolding by their stepfather or stepmother.

“All this Jesus takes on himself this very night. Or think of the young farmworker or the laborer who has no job or suffers some infirmity. Not all is joy tonight. There is much suffering. There are many broken homes. There is much pain and poverty.

“In taking all this upon himself, the God of the poor is showing us the redemptive value of human suffering. He is showing us the value it has for redeeming the poverty and suffering that is the world’s cross.

“In Mexico, Pope John Paul II said that devotion to Mary is not for the weak of heart. Mary knew how to endure flight into exile, marginalization, poverty and oppression. She saw her son taken prisoner and tortured. She saw him die unjustly on the cross.

“Mary cries out in holy defiance, declaring that God ‘will send the proud and the arrogant away empty-handed and, if necessary, bring the mighty down from their thrones. At the same time, he will give his grace to the lowly, to those who trust in his mercy’ (Lk 1:52–53).

“How I wish that that child, nestled in straw and humble cloth, would speak to us this Christmas of the sublime value of poverty! How I wish that all of us who are reflecting here would bestow divine value on our sufferings, great and small!

“Starting tonight, let us be more intent on offering to God whatever we suffer. Let it be joined with the sacrifice of the altar and be made into a host that redeems and sanctifies our lives, our homes, our society.

“If only we knew how to accept today the message of that poor, humble child who gave himself totally to save the world!

“Let us remember the child who was born in a manger and wrapped in cloth so that our poverty, our pain, and our suffering would make sense to us. Let us remember the child whose crib reminds all of us that our destiny is the glory of God in the highest heavens.”

As I prepare to celebrate Christmas with family and friends, I ask myself, what can I do for those who will spend the day on the street, on park benches, in refugee detention centers, alone and abandoned?

One idea: I could reduce my Christmas budget and help a non-profit that takes care of the destitute and marginalized, not as an act of charity but as an act of justice.

What’s your idea?

With materials made available by the Archbishop Romero Trust. Read or listen to the homilies of St Oscar Romero at romerotrust.org.uk.