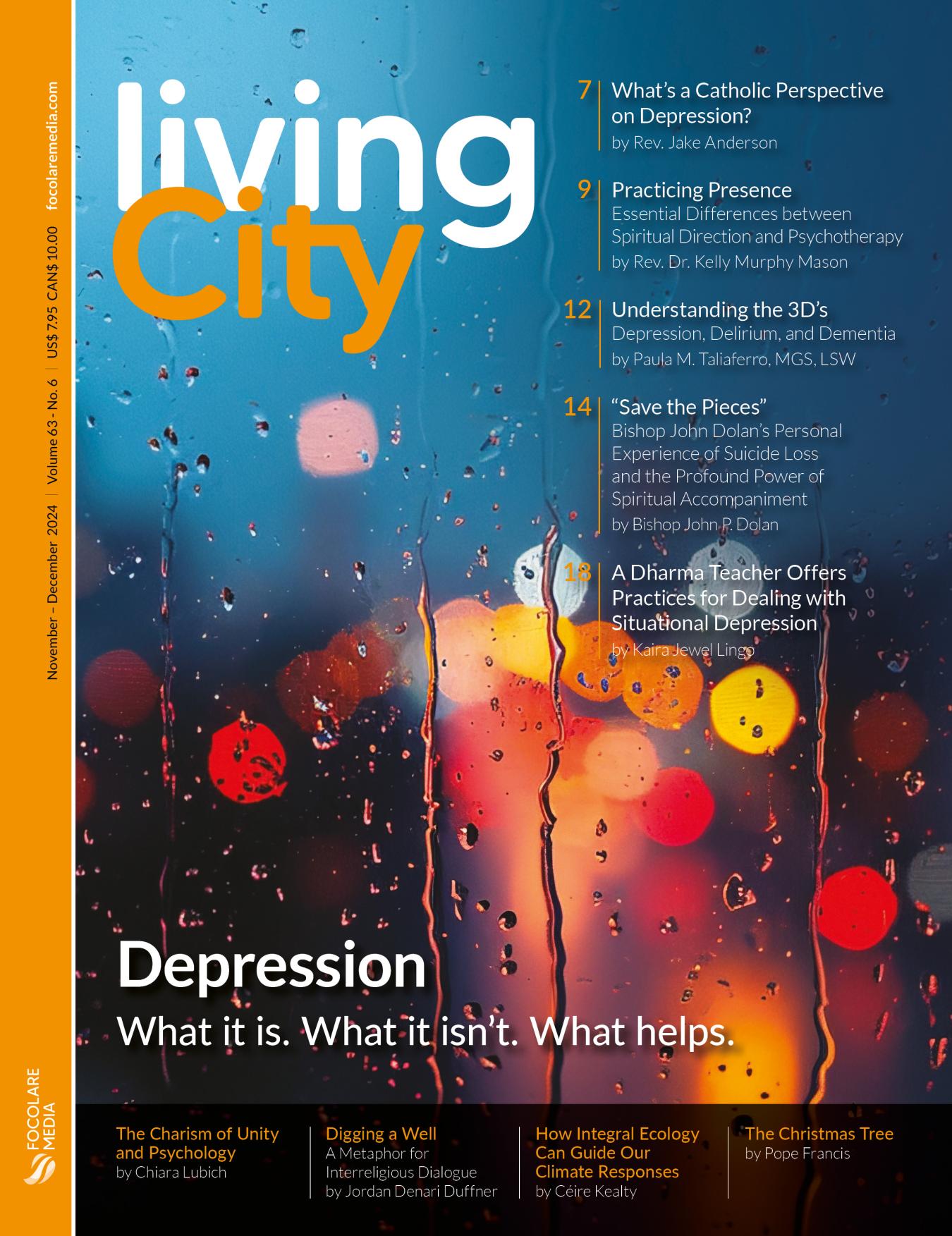

Photo by Valiantsin Suprunovich | Dreamstime.

When I was a psychotherapist in private practice, people would often seek me out because of my background in pastoral counseling and spiritually-informed treatment. Now that I serve as a spiritual director, people seek me out because of my clinical experience. While I believe psychotherapy and spiritual direction can be mutually informing as helping-healing modalities, I also recognize them as necessarily distinct.

Whenever I start with a new directee, I’m explicit that we will not be doing therapeutic work, although certain insights and realizations might emerge over time. We have another focus: we allow their spiritual concerns to remain central to our unfolding conversations.

People tend to be more informed about what psychotherapy involves, so there’s not much orientation at the start of that process. My therapy clients expected we would generally meet once a week for forty-five to fifty minutes, focusing on their presenting issues, whatever those might be: depression or anxiety or conflict in significant relationships or a different concern altogether. We would identify goals and then explore opportunities for improving outcomes, diminishing distress, and promoting personal growth. We would take note of progress when it occurred and strive to go on making progress.

Spiritual direction is not nearly as goal-oriented. My working definition is straightforward: In spiritual direction, we direct our attention to the spiritual dimension of our lives—with the clear and sacred intention of becoming increasingly aware of what it has to tell us about living wisely, purposefully, and well in the days we are given.

Customarily, director and directee meet once a month, from fifty to ninety minutes per session, although they may meet biweekly in the midst of a crisis. Spiritual direction sessions offer people less specialized support than therapy does. We invite a certain spaciousness in the interpersonal engagement, leaving plenty of good room for the spirit to move where it will—between and within director and directee.

Also, ongoing spiritual direction does not insist on progress. Rather, it encourages the routine practice of presence.

I started serving as a spiritual director a few years ago, in the midst of a pandemic, when people everywhere were facing crisis. Most of the directees I’ve seen have therapists of their own, and most of these therapists are not inclined to discuss their spiritual yearnings or realities. Borrowing from clinical parlance, I would say that I help directees connect to their individual spiritual supports and tap the spiritual resources available to them. My directees often take stock of their spiritual practices, beliefs, traditions, and commitments and then consider how those may or may not serve their continued spiritual development.

Also, ongoing spiritual direction does not insist on progress. Rather, it encourages the routine practice of presence.

The understanding of spiritual direction has expanded considerably in recent years. It is not solely a discipline for clergypersons or monastics interrogating or confirming their vocations; its scope is not even confined to Christian contexts. I’ve worked with Hindu and Jewish directees as well as Catholic and Protestants ones, in addition to people who consider themselves multifaith or interspiritual. Some of my directees are religious professionals, others are lay leaders, and others are sincere seekers after something they have yet to find. Each person faces unique spiritual challenges.

When I first began meeting with my own spiritual director fifteen years ago, I was in ministerial formation. I’d drive to the Rose Hill campus of Fordham University and wait for her in one of the tiny pews in Blue Chapel while she tried to locate an empty classroom where we could meet privately. In those empty classrooms, my director taught me more about spiritual direction than either my training program or apprenticeship did, because she showed me how to experience my spiritual experiences (rather than narrating or performing or conceptualizing them), and how to stay present to the essentials they surfaced.

Nowadays, we meet virtually. Purportedly she has retired from active ministry and one of these days, I suppose, I should actually let her. Yet spiritual direction relationships are fabled for spanning years and sometimes decades. For an hour or so each month, she shows me a much tougher love than any other helping-healing professional has, a tougher love and probably a better one. She has stayed closer to my various heartbreaks and heartaches for longer than any of them dared, far closer at times than felt comfortable. Thank God she never made it her aim to make me comfortable. Thank God she has stayed so faithful.

For the past couple years now, I’ve mentored apprentice spiritual directors through an online program and I’ve observed that one of the hardest habits for them to break is a drive to make directees feel good, and to offer them some sort of obvious therapeutic benefit. As nice as this first seems, it’s ill-considered to attempt mitigating every degree of discontent. This is to never get below the surface of things, or get to the heart of what it means for us to be fully human as we wrestle with our angels and our demons alike.

There’s no known cure for a dark night of the soul, only patience and compassion in the face of it and the slow forbearing of its indeterminate duration. Every day is not Easter Sunday, I tell myself. Sometimes it’s Good Friday instead, or Holy Saturday, when everything is silent as the grave. Each is sacred unto itself.

There’s no known cure for a dark night of the soul, only patience and compassion in the face of it and the slow forbearing of its indeterminate duration

While not all my directees identify as Christian or believe in the Resurrection, I notice that every one of them has had to die to something in their lives, and every one has also somehow risen again. Their lives all have something to proclaim; I simply bear witness.

Spiritual directors have to develop a keen appreciation for the futility of playing God. We need humility to do our work as honestly as possible outside of any set timetable. We must countenance surrender and acceptance as vital spiritual disciplines. Individual agendas can be so stubborn and subtle; we see that in our directees as well as in ourselves. But they will out in the end, and they can be released most readily when we recognize them for what they are. Spiritual directors notice and name them in session after session.

Other interventions have little place in spiritual direction. Directors cannot stay as busy as most psychotherapists are in an effort to improve outcomes, but directors can succeed in doing the thing that matters most: attending to the spiritual dimension of peoples’ lives as completely as possible, honoring their struggles as well as their peak experiences. And in time, directees learn to recognize what is true of and in their lives, how it is being revealed, and why they might reverence that.

Jesuit theologian Walter Burghardt once characterized a contemplative approach to life as “a long loving look at the real.” The longer we can look at the real, the more we will notice its pronounced contours. As directors, we take care to keep the real in our sights. Some of the most momentous sessions involve a director merely echoing and amplifying something a directee has said, or mirroring an image or scene they’ve just described, often using identical phrasing. Suddenly someone can hear their own voice and recognizes the ring of truth in it. With practice, directees come to sense their own ability to provide authentic witness to things seen and unseen in the world.

We all can exercise our capacity for transcendence—seeing above, below, through, and beyond the surface presentations of things—and in doing so strengthen it. If we neglect to exercise that capacity of ours and instead endlessly engineer and optimize our existences, we’re gradually diminishing our capacity for transcendence, as well as the access it grants us to divine indwelling.

As a spiritual director, I believe that we are most alive when our self-concept is not limited to who or what we appear to be in our sociocultural context or to the outside world. We can choose to explore the holy ground of our interior (sometimes called “soul”), where the realm of God declares its sovereignty. We don’t need to measure the sum of our success using conventional metrics. We can indeed keep our spiritual concerns the central ones in our lives.

If you enjoyed this article, you might like...