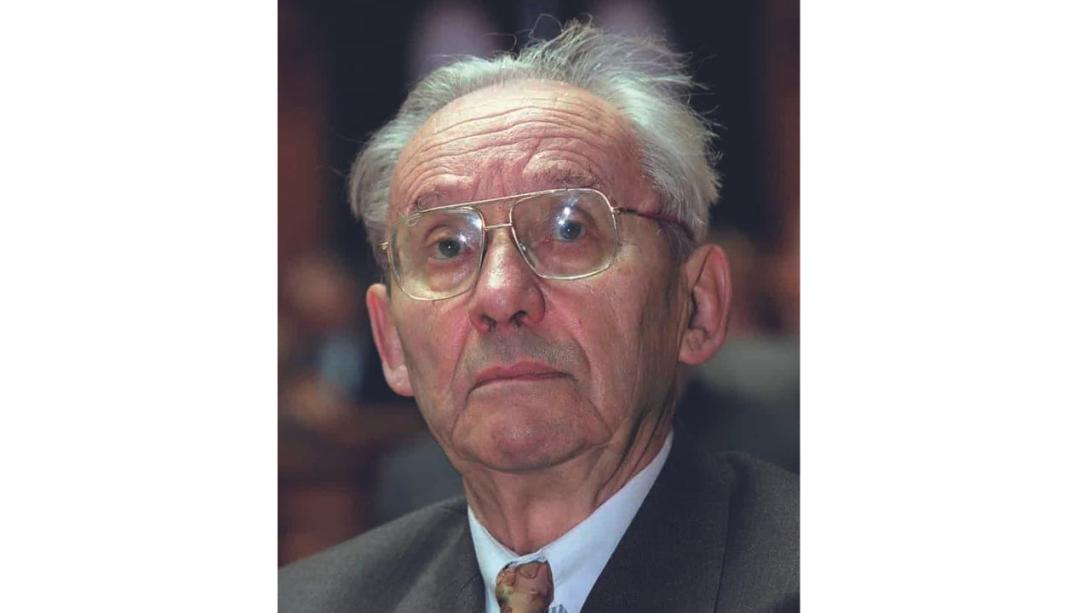

Photo by Juerg Mueller / Scanpix

French philosopher Paul Ricoeur (1913–2005) was born in Valence, Drôme. He came from a devout family of Huguenots (a Protestant minority). He was orphaned at an early age—his mother died shortly after his birth, his dad was killed at the start of World War I, and he was raised by his grandparents.

He was a devoted student, reading the great classics and going on to study philosophy. Paul studied at the University of Rennes, but he recalls how his failure to pass the entrance examination for the Ècole Normale Supérieure marked him for a long time (‘Intellectual Autobiography,’ 6). He tells how the Second World War caught him by surprise at the end of a beautiful summer spent with his wife at the University of Munich attending a German language class.

He ended up being drafted, became an officer and was imprisoned for five years. During his captivity he read the works of Karl Jaspers. Ricoeur explains how he and his fellow prisoners knew nothing “of the horrors of the concentration camps” until their liberation in the spring of 1945.

Paul joyfully returned to his family and taught philosophy at high school for some time while doing his own writing and research.

He had met Gabriel Marcel in Paris before the war and was greatly influenced by him, saying that what he learned from Marcel was “always to supply examples. If you want to talk about justice, ask yourself why something is unjust” (Philosophy, Ethics and Politics, 130).

He was appointed to teach at the University of Strasbourg and then went on to the Sorbonne. Ricoeur served as dean at the University of Paris, but these were difficult years for him because of the student riots of 1968. He lectured widely in the United States and Canada, teaching for some years in the University of Chicago.

He participated, along with Levinas and Kolakowski, in the summer philosophy roundtables organized by Pope John Paul II at Castel Gandolfo, Rome. President Emmanuel Macron of France was actually an editorial assistant to Ricoeur.

The human person: capacities

Ricoeur places great emphasis on the notion of capacity when it comes to understanding who we are as human beings. There is the danger of seeing humans only in terms of their performance. Indeed, we might be familiar in the world of education and business with the term “KPIs,” that is, key performance indicators used in quality assurance projects.

He says that our society is still one in which we measure people on their performance, not their capacity—some of which have been stifled by society, life or illness. He argues how his approach is to find what he calls “the capable human being behind the ineffective human being, behind the powerless human being.”

Ricoeur emphasizes how “it is in the capacity to be human that the character of being deserving of respect lies.” An interviewer once mentioned how in French children’s class books “disabilities are almost never taken into account, or even mentioned, as if they were some sort of taboo.” Ricoeur agreed saying, “Yes. It is true that we don’t see the lame or blind in children’s books.”

It is the case that in Victor Hugo’s famous novel you have sympathetic characters like Quasimodo, the hunchback of Notre Dame. Nonetheless, Ricoeur points out that you will not often find those “with physical or mental disabilities… because they frighten children.”

He tells how when he was in Canada there was the thalidomide scandal. His friend at the University of Montreal oversaw the orthopedic equipment for children who had no arms. The children learned how to use their feet to write, but the teachers rejected this because “it was too distant from the human form” (‘Ethics, Between Bad and Worse,’ 129–130).

Ricoeur points out how the view was “if there is no resemblance to the human form, it is unacceptable to children.” So, incredibly complicated devices were used, while it would have been simpler for the children to use their feet.

Our fragility

The main theme of his work Oneself as Another is the suffering human being, who is, he holds, notwithstanding all, “the capable human being.” The human person is, of course, a being “capable of speaking, capable of acting, capable of promising.”

But he or she is much more than this: “The first maxim of my action is that ‘any other life, by reason of its capacities, is just as important as mine’” (‘Sketch for a Plea for the Capable Human Being,’ 18–19).

Ricoeur gives an account not just of our capabilities as human beings but also of our weaknesses and fragility. He once wrote a short reflection to psychiatrist friends titled La souffrance n’est pas la douleur (Suffering is not pain), outlining how suffering reaches us as human beings “in the entire panoply of our capacities,” that is, in our “power to be” and not only in our “power to do.”

Psychoanalysts may, for example, encounter in patients the incapacity to tell their story because they may be “overwhelmed by memories that are unbearable, incomprehensible or traumatic” (119). But the recognition of this incapacity to communicate their story is, in fact, a capacity opening what it means to be a human person.

Part of the paradox of who we are “over and against” the affirmation of our capabilities is the “confession of our fragility.” It is “the inability-to-say, in all its forms… [which] is the first mark of fragility.” Illness, old age and disabilities are all instances of such fragility, but they do not unmake us as human persons (Philosophical Anthropology, 250–251).

Ricoeur speaks of the condition of the “wounded cogito,” which is the realization that we are not, in fact, masters of ourselves. He describes how in today’s world we are “under the threat of a claim, and appeal not to suffer, an appeal not to be sick, and even the formulation of a right to health.”

He sees this as leading to the idea that medicine is required “to shelter me from suffering” (‘Ethics, Between Bad and Worse,’ 119).

According to Ricoeur, there is not necessarily a contradiction between happiness and suffering. He understands happiness as “the capacity to find meaning, satisfaction, in self-accomplishment,” but this does not exclude suffering. By suffering he does not simply mean pain: it is, he believes, “the reduction, even destruction of the capacity for acting, or being able to act.”

Giving until the very end

Speaking at a medical conference in Paris, Ricoeur referred to the human action involved in palliative care. He recalled the words of a Danish philosopher who said, “what remains human, the last glimmer of the human, is the capacity to enter into relation, ‘giving and receiving.’”

Ricoeur stresses how it is important to live in the reality of “giving and receiving… [even] when one can no longer do anything.” We must, he says, defend this “capacity of exchange in giving and receiving in the seriously ill patient to the very end.”

Speaking to the medical professionals at the Paris conference, Ricoeur reflects on what they receive from the gaze of their patients. It is, he argues, the appreciation “of your own humanity.”

Blessed Chiara Badano, a young Italian girl in the Focolare who died at the age of 18 from bone cancer, is an example of someone going beyond the wound, the pain of her condition. In a letter she wrote how “now nothing healthy is left in me, but I still have my heart, and with that I can still love.”

She was equally able to live receiving. She wrote, “I don’t really do anything at all! On the contrary, it’s all of you who are a help for me.”

Hers is, I believe, an example of the living out of what Ricoeur called the capacity and fragility of who we are as human beings.