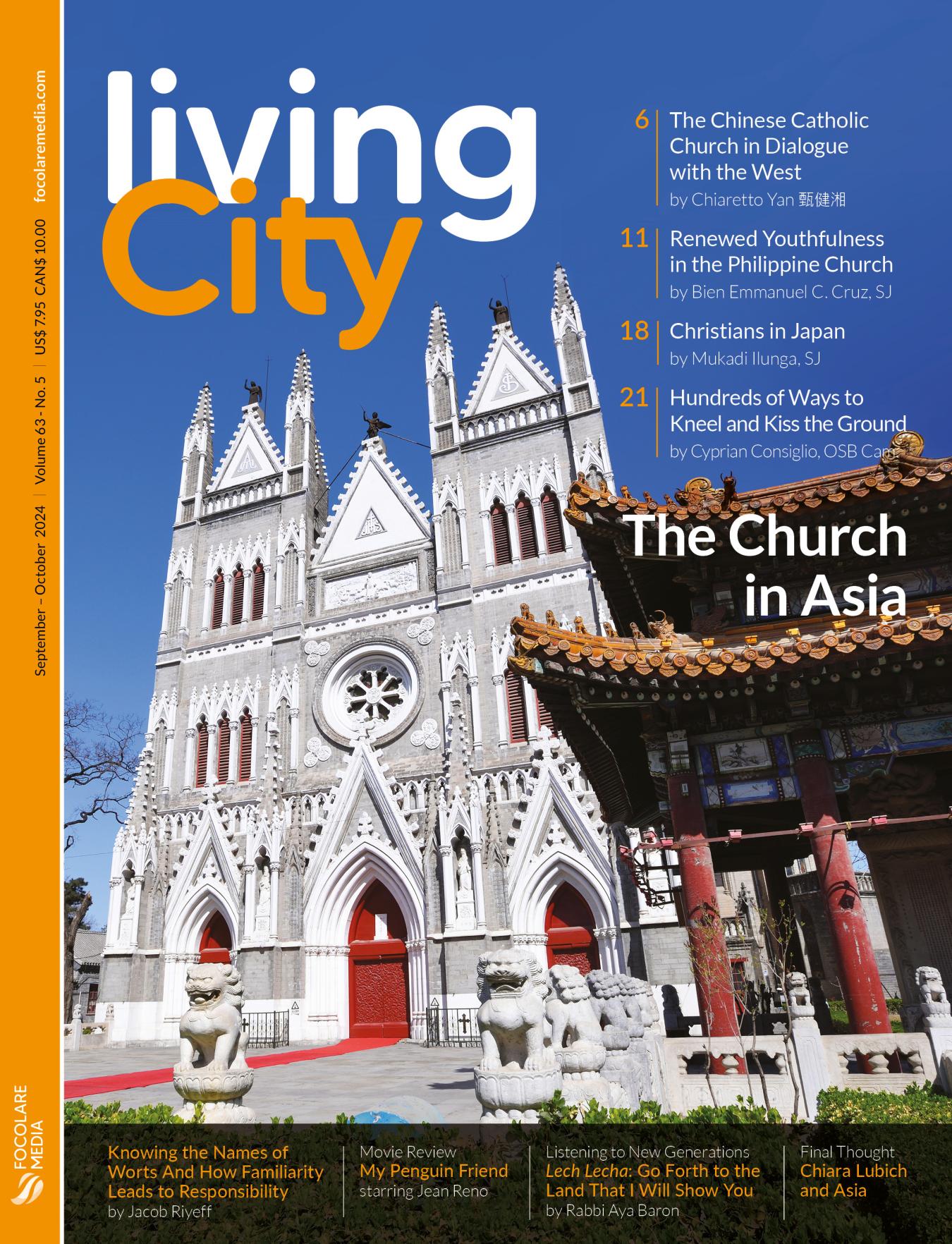

Photo by WaitforLight | Adobe Stock

Pope Francis greeted Cardinal John Tong Hon, bishop emeritus of Hong Kong, and Cardinal-elect Stephen Chow Sau-yan, SJ, bishop of Hong Kong at the Sunday Mass on September 3, 2023 during his visit to Mongolia. The Pope said: “I would like to take advantage of their presence to send a warm greeting to the noble Chinese people. I wish all the people the best, and to move forward, always progress. And I ask Chinese Catholics to be good Christians and good citizens.”

It was Pope John Paul II who first appealed to the Chinese people to be good Christians and good citizens, a call now echoed often by Pope Francis.

In the last century, Catholic evangelization in China was common, when missionaries went under the protection of Western powers. China suffered “a century of humiliation” at the hands of Western powers and Japan. And since Vatican II, Catholic interreligious encounters have usually meant dialogue—talking with Jews or Muslims, contacts with Buddhist or Hindu leaders; but there has been very little Catholic exposure to Confucian or Daoist thought and spirituality.

Let me offer five approaches to understanding the Church in China today.

A Dialectic of Harmony

Chinese culture is a blend of Confucianism, Buddhism, and Daoism, which complement one another and contribute to the happiness and harmony in daily life. Confucianism is a social and moral philosophy that focuses on personal relationships and present-day fulfillment. Buddhism contributes a sense of religious spirituality. Daoism is more transcendent and mystical, with attributes of the invisible, the inaudible, and the formless. Dao manifests itself as absolute and united One; it contains the yin and yang, and where One becomes Two. Two becomes three in the Qi, the relation between the vital forces of yin and yang. I call this a “dialectic of harmony,” and find similarities between it and the dialectic of love of Chiara Lubich.

In the dialectic of love of Chiara, Jesus forsaken on the cross, instead of denying the Father, lives a total self-denial in his kenosis, entrusting completely to the will of the Father. In Daoism, there is a dialectic of harmony, with dao-de, yin-yang harmonizing, being-nothingness mutually generating. To my mind, this dialectic of harmony is a good disposition to understand Trinitarian relationships. We can interpret the love between Father and the Son in the Trinity with the relationship of Dao-De-harmony.

An Integral Ecology

Daoism reminds us of our relationships in the creation. Daoists were the first ecologists because they believed that nature itself is divine and people should live in harmony with it, blending in with the environment, and doing no harm.

China has developed from a backward economy and industrialized in recent decades. The world knows well that the pollution was acute, but few are aware that air quality across China has improved in recent years due to countless, large-scale green initiatives. It has the duty now to share its experience to developing countries for striking a balance between economic development and environment protection. I have seen up close these misunderstandings, for instance, when I served as the coordinator of the Holy See Pavilion at the Beijing Expo 2019 on Horticulture.

Pope Francis’ Laudato Si’ argues that we need integral effort to combat the ecological crisis. The book of Genesis says humans are created in God’s image. The notion of absolute domination (Gen. 1:28) over nature and other creatures is a distorted interpretation. We should be caretakers (Gen. 2:15), to glorify God with other creatures.

Humans have disobeyed God and ruined harmonious relationships between humans and God, between themselves, and with nature. This selfishness is what has led to the ecological crisis. Instead of a distorted anthropocentrism, an “anthropocentrism of Christ,” Jesus, the new Adam, through the Cross, restores the three-fold harmonious relationship.

Although it has no mention of God and creation, I found consonance between the spirit of Laudato Si’ and the inauguration speech of President Xi Jinping, who emphasized scientific policies and research to create a harmonious ecosystem, following laws of nature, and referred to the earth as “our common homeland.” The rise or fall of a society is dependent on its relationship with nature. Industrialization generated material wealth, but damaged nature.

We live in a community with a shared future. We need collaboration to tackle environmental issues, to have a balanced ecosystem, to accelerate an “ecological civilization,” and to work together. President Xi Jinping spoke also of a shared responsibility toward future generations.

We can interpret the love between Father and the Son in the Trinity with the relationship of Dao-De-harmony.

Fraternity and Social Friendship

The concept of fraternity and love in Chinese is expressed in the following terms: Ren’ai has a connotation of benevolence and human-heartedness; Jian’ai, an all-embracing love; and Bo’ai, a classical term influenced by the concept of agape in Christianity, made popular by Dr. Sun Yatsen, the founding father of modern China, to express the idea of universal love and fraternity.

The relationship of fraternity is also expressed in an idiomatic expression: “a relationship as close as one’s hands and feet.” In recent years, President Xi has stressed that fine traditional Chinese culture, including values of you’shan, friendliness and fraternity, are alive in the people’s hearts. This friendship not only applies on a personal level, in social relationships, and among nations in a community of common destiny for all.

In Christianity, brotherhood is intrinsic to the meaning of fraternity in Christ, manifested in sharing of goods in community and helping the poor. This contributed to the abolition of slavery. But throughout the twentieth century, freedom in liberalism (or equality in socialism) were emphasized and the real meaning of fraternity was almost lost.

Pope Francis signed a joint declaration, “Human Fraternity for World Peace and Living Together,” with Sheikh Ahmed el-Tayeb who represented the Muslim world at Abu Dhabi in February 2019. The Pope has a gradual approach recognizing that all are to live fraternity in the one human family. Faith in God is the starting point, and the benevolent gaze of God includes each person in the human family.

This is consonant also with Confucian tradition, in which relationships start within the family: “Honor the elderly and care for the young in other families as we do to those in our own” (Mencius 1A7). Such relationships then extend to distant members of society: “Now the man of perfect virtue, wishing to build up himself as such, seeks to build up others as well; wishing to enhance himself, seeks also to enhance others” (Analects 7:2). As Pope Francis said in Abu Dhabi: “This fraternity is destined to extend to people of all religions and cultures.”

A New Model of Economy

China has lifted more than 800 million out of poverty in recent decades. In my forthcoming book, I give a historical overview of poverty alleviation in China, and identify efforts for reform—for example, systematic agreements by which more prosperous coastal provinces assist the poor provinces in the interior.

China’s approach to alleviating poverty can be taken as a new economic paradigm incorporating Asian values of harmony, diligence, frugality and habitual savings, emphasizing education, political stability, and pursuing continuous reform. China has worked out a development path that is consonant with its culture. Their experience is an endogenous development model for developing countries in the sense that each country should find a model suitable for its own conditions and development.

On the other hand, there are challenges of spiritual poverty due to rapid economic development and social changes, i.e., materialism, worship of money and a culture of indifference. The Chinese government has recently banned for-profit after-school tutoring, a measure for reducing overstress and competition for kids, youth, and even parents. But there remain problems. Before the Covid pandemic, many Chinese were going abroad, and international student exchanges should be encouraged once again. In universities, science, technology, and business studies should be balanced with humanities such as literature and language studies. In my book, I quote Chinese classics and poetries by Zhang Zai and Tao Yuanmin as well as biblical narratives and wise sayings. Modern poetry should also be encouraged, as reflections leads to interiority and dialogue about transcendental reality. This is all consonant with the Chinese tradition of forming an all-around person.

If you enjoyed this article, you might like...

Freedom of Religion and the Golden Rule

The Chinese constitution does allow freedom of religion, but not political intervention. This complicates efforts at evangelization. Christianity has deep roots in China since the days of Matteo Ricci; but growth in recent decades of Christians are mostly Protestants—they do not owe allegiance to a “foreign power” in Rome as Catholics do.

China is cautious that religions should not develop extremism, and no foreign interference to use “religious freedom” as a pretext to destabilize the order of things. Interestingly, this obstacle is not mentioned anymore now in relation to the Holy See, but is rather referred to the U.S.

Both Jesus and Confucius spoke of the Golden Rule on reciprocity. Confucius used the passive form: “Do not do to others what you would not want others to do to you.” It is deemed more practical as conduct not to harm others while reciprocal love is more demanding. Meanwhile, on the Church’s mission in the world, the Holy Father has repeated on numerous occasions that evangelization is not “proselytism,” and that the Church grows “by attraction” and “by witnesses.”

Institutional dialogues between China and the Holy See have been going on since 1986. There has been significant improvement of relations including a historical agreement on September 22, 2018 regarding the nomination of Chinese bishops. Pope Francis readmitted eight Chinese bishops ordained without the Pontifical Mandate, making all Chinese into full ecclesial communion with the Holy See. In the following two years, seven bishops who were secretly ordained without government recognition were allowed to take office with a “ceremony of officialization” and have been recognized by civil authorities. Since then, there have been eleven more Chinese bishops ordained according to the framework of the agreement.

It is a complex issue with both benefits and drawbacks. It faced criticism and skepticism, particularly from those concerned about religious freedom in China, saying that the government exerts too much control over the Church. But the agreement provided a framework for addressing other issues related to religious freedom, such as the recognition of Catholic communities and the protection of Catholics’ rights to practice faith without interference. By reaching this agreement, the Vatican gained a say in the appointment of bishops in China, while the Chinese government acknowledged the Pope’s authority in the Catholic Church. This represented a significant step towards the normalization of relations and opened up possibilities for increased cooperation on various issues of mutual interest.

Hope, Challenges, and Opportunities

Each person has dreams, and we all have aspirations for all people as a collective dream. I dream of a world of fewer wars and conflicts, less hunger and indifference, the reduction of poverty and greed. More than competition, we need collaboration. More than wit, we need tenderness. I dream of respectful dialogues among people of different cultures, faiths and convictions, recognizing that diversity in harmony can be a gift for one another. I dream of a world, a common home for all, for generations to come, with fresh air to breathe, and for young people to travel freely for exchanges, and appreciation of each other’s history, culture, art, and literature.

Christians are called to be instruments of peace. I hope that Catholics in China, small in number but aware of their historical responsibility, may change the landscape of the Catholic Church in due time. I also hope that the dream of Pope Francis for the Church and the dream of President Xi for the Chinese people can converge and bear fruits.

It is coming of age for China to take a more important role to dialogue in equal footing with the West. Both the United States and China need to revise inaccurate prejudices. The universal Catholic Church with no political and economic interests can facilitate this process. My wish is for the West and China to know each other better. There could be a three-point dialogue: China, the West, and the Catholic Church. Since China and the Catholic Church are the two oldest extant cultures in the world, their dialogue and collaboration could be a game-changer and contribute to world peace.

As a follower of the Focolare Movement founded by Chiara Lubich, I believe in the charism of unity, building a united world beyond all borders. This corresponds to the profound needs to people of all cultures, and, particularly to me as a Chinese.